In an April 18, 2011 interview with Constance Chatfield-Taylor, Mike Copperthite unveiled one of the greatest forgotten stories of Georgetown. His great-great-grandfather, Henry C. Copperthite, a farm boy from Connecticut, was stationed at Georgetown College during the Civil War. After returning to West Washington as a newlywed with his young wife, Johanna, they decided to settle and began a small baking shop called H. Copperthite Pie Baking Company at 1407 32nd Street Business boomed and soon the company was churning out over 50,000 pies each day in Washington at their factories on Capitol Hill and in Georgetown on the corner of M Street and Wisconsin Avenue.

As his company grew, so did the Copperthite influence in Washington. Henry Copperthite owned part of Analostan Island (now Theodore Roosevelt Island), constructed many of the wood and brick houses in Georgetown that were built between 1880 and 1925, and was a large supporter of horse racing in the Washington, DC area (he sold a racehorse to Cornelius Vanderbilt for a record sum). As a fifth-generation Washingtonian, Mike Copperthite shares the story of his family and gives insight to an amazing man in a true rags-to-riches story.

Constance Chatfield Taylor: We are recording and we’re here today on April 18, 2011 with Mike Copperthite. You can correct the pronunciation because it is a difficult one. My name is Constance Chatfield Taylor. We’re doing an interview for Oral History for the Georgetown Citizens Association. First of all, is it Mike or Michael?

Mike Copperthite: It’s Mike.

Constance: It’s Mike and can you please give us the correct pronunciation of your name and actually your birth date, place and day of birth.

Mike: Right. My name is Michael Clay Copperthite and I was born in Columbia Hospital for Women, which is outside of Georgetown, if you know real Washington, January 6, 1956.

Constance: And we’re doing the interview here in the Peabody Room. Michael’s… Mike’s family history in Georgetown is very significant. He is here today to primarily talk about his great grandfather. Mike, if you can kind of introduce him to us and tell us when he was born, when he arrived in Georgetown and what brought him here?

Mike: If you don’t mind, I’m going to read because I wrote all this down and I’m not really good in oral presentation so…

Constance: That will be just fine.

Mike: OK. I am the son of Robert Crittenden Copperthite who was born on 12/29/1929, the grandson of Andrew J. Copperthite who was born on 1903 and passed in 1975, and the great grandson of Henry C. Copperthite, Jr., born in 1878 and died 3/3/1911 and the great great grandson of Henry C. Copperthite, born December 5, 1846 and died October 13, 1925. All of these people are from Georgetown. My daughter who’s downstairs, Keely Alexa Crittenden Copperthite, born in December of ’97, is a sixth‑generation Washingtonian on one side of the family. On the other side, we go back to Jamestown and pre‑date people arriving in the colonies.

On a personal note, we have ancestors of the American‑British conflict and this month, we buried our twenty‑seventh relative, my father‑in‑law, at Arlington National Cemetery, who served in World War II.

Henry C. Copperthite came from the British West Indies, Antigua at 18 months to Meridian Connecticut with his parents in 1847 to farm. Henry joined the famous 79th Highlanders of New York and was a private, who came to Washington and was stationed at Georgetown College for training and the protector of the university. That was his first visit.

The 79th fought in skirmishes at Bailey’s crossroads in Virginia before engaging in major campaigns at the Battle of Manassas Bull Run I and II, Fort Sanders, Knoxville, Tennessee and Antietam. Henry Copperthite was at Appomattox Courthouse for the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s army or the Potomac and then marched down Pennsylvania Avenue for the Grand Review before returning to Connecticut as a citizen of the United States.

The skills of a wagon driver that Henry learned, he took back to Connecticut were highly prized in the day of apprenticeship. He started delivering for a baked goods company. He decided even though it paid less, he would learn the baking trade and over the next 20 odd years, Henry became familiar with every aspect of what was about to become the explosion in the dessert, food storage, transportation, grocery store, sanitation and marketing of mass goods to the general public.

Constance: And what year was that approximately?

Mike: That was between 1863 and 1870. In 1870, while on his honeymoon, Henry and his wife Johanna O’Neil, born in January of 1850 and passed on in February of 1921, visited West Washington, which is now Georgetown and determined that will be a great place to start a business.

In 1885, they returned on the eve of Thanksgiving with a wagon, a horse and $3.50 to their name. He started baking pies and returned a one‑day profit of about a hundred dollars in today’s money. On January 1, 1887, the H. Copperthite Pie Baking Company began with his new partner‑investor, T. S. Smith at 1407 32nd Street in the northwest and the newlyweds never looked back.

25 years after launching the Connecticut‑Copperthite Pie Company in Georgetown, Henry and his family, most of them came to Washington, along with many of his Civil War friends, to help run his business were producing over 50,000 pies a day in Washington alone, with factories in Capitol Hill, M Street and in Wisconsin Avenue here in Georgetown.

Soon he purchased the bakery in Hartford where he first started the dessert business craft giving him factories there and in Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, Petersburg, and Newport News, Virginia. In the day and age when the home delivery, shopping for groceries and delivery of fresh baked goods was in its infancy, Henry Copperthite was a pioneer.

He provided pies to the White House, Congress, the Supreme Court, the Federal Government, becoming one of the largest manufacturers and purveyors of desserts in the United States. Our family provided pies and hard tack dough for the Doughboys training and fighting in World War I. On average, every man, woman and child in the District of Columbia ate two of his pies every seven days.

He initiated a unique print and ad campaign directed at the housewife with tips on how to save work and time while extolling the virtue of eating pie with patriotic and whimsical slogans and caricatures of “the pie man from Connecticut” and in an era where most advertising was the presentation and printing of the business card.

Henry placed the ads in all five daily papers in Washington in almost every day for some 30 years. Television, radio, tweeting, Facebook, and email had yet to be invented but “the man from Connecticut” or his products were known to most people in America for a longer time than just about anybody.

Just a casual search online of the Library of Congress pulled hundreds of articles about Henry Copperthite from the Georgetown news: society events, news accounts of his travels, charitable activities, satire on how fat he was getting from pie and the “leading pie town,” etc. In the sports section of the news where he was at the top of one of the three most popular sports at the turn of the last century – pacing and trotting horse racing.

As the pie baking demand grew, Henry acquired large tracts of land in Fairfax and Loudoun County. He purchased 600 plus acres at Burke Station, Virginia around 1900 for dairy production to make fresh pies and over 5000 acres in Loudoun County, some of it is what is now Runnymede Park, for fresh foods and vegetable.

He also acquired land in Rock Creek Park, several lots in Georgetown throughout the city. Henry brought land in Alexandria County which is now Arlington, Virginia and he owned Analostan Island which later became Theodore Roosevelt Island.

In Burke, Virginia, his summer getaway, he built one of the “finest race tracks in Virginia” with stables for 75 race horses, grandstands that seat 2,000 plus guests with four hotels and stores for shopping and entertaining. It became a place for nature spectators, sporting and family events occurred in the summer months with thousands of folks from all walks of life flock from the city to participate.

He held match horse races, motorcycle races, car races, dance contests for the social elite and the average citizen. President McKinley boarded and raced his five horses there as well as Mr. McLean, the family that once owned The Washington Post.

Trains ran from Union Station, Georgetown, Alexandria and Richmond, Virginia for people to come from Memorial Day to July 4th to witness boxing events that featured Jack Johnson, exhibition baseball games with Ty Cobb and the Senators, witnessed one of the first if not the first flight over sports venue on Memorial Day in 1909 by the Wright Brothers.

Until probation and elimination of track side gaming, the decline of the horse and the rise of the car for transportation, Burke Virginia was the go‑to spot for the weekend getaway from the city’s oppressive heat.

Henry was an inventor, holding patents for communication devices for speaking between cars and trains and inventing a pie safe to keep baked goods fresh. He co‑invented which today is the disc brake He worked on several other products which made it into everyday use.

One of his employees sold to Kraft which is one of their famous mayonnaise formula. Today, most of the milk bought locally in the Washington area come from his partners and his business colleagues’ dairies and farm.

Henry was a founding board member of the newly revived Potomac Savings Bank at the corner of M Street and Wisconsin and gave loans to working class people at a time when the banking system mostly ignored these folks.

He built several homes in Georgetown for his family, his workers, himself and to sell to the public. Many brick and wood structures and homes that are over a hundred years were built by Henry and his wife looked much after that side of his business.

On Copperthwaite Lane, now South Street, where the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Georgetown is today, were two historic trust homes from the city’s first mayor which were purchased and preserved by the Copperthite family.

Henry Copperthite was a wagon driver and his pies were first delivered by horse‑drawn cart, then later by truck. His delivery wagons were in almost every parade of the city during his time and were part of the Inaugural events of his friends and fellow Masons William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt.

Today, one of his wagons is in the Smithsonian Exhibit of Natural History and a truck he gave to the College Park fire department is still on display. As the union movement matured, his company was spared by strike and deliver transportation union which he helped found, which is now known as AFL‑CIO.

Henry served in the city’s Centennial Commission, Georgetown’s planning board, supported Home Rule, and raised and gave hundreds of thousands of dollars for the support of Liberty Bonds, provided food for needy, donated to charity and supported Veterans’ Pensions.

Along with Harriet Beecher Stowe, he was a founding member of the Connecticut Humane Society for protective services of children in the workplace and home and to insure the welfare and prevention of cruelty and proper treatment of animals.

He was a member of the Columbia Club, the premier sports club for the city where cycling, rowing, trap and skeet, fishing, football and baseball and other sports. He raised and gave funds for the speedway, a new drive to rival Park Avenue in New York which is now the scenic drive along Potomac Park.

He helped secure funds for the establishment of public beach in 1913, the Tidal Basin Beach facility. He was a shareholder and board member of many companies including the Chesapeake Dry Dock Company which is now the Newport News shipbuilding company, where his baked goods went off to American soldiers abroad.

As a member of St. John’s Church, that was where his family were married and had services for the family in their passing. In his life, he contributed substantially to the restoration and construction of that church.

During all these, his companies continued to grow. Before the Depression, stock in the Connecticut Pie Company traded in 147 dollars per share and after the Depression, they were still trading at 140 per share. Heurich Brewing, another well‑known company in Georgetown, was trading at around 40 dollars per share.

His company was the second largest non‑government‑related employer in the city. His baking empire became part of the Ward Baking Company in New York (now, Hostess brands of food, Wonder Bread and C.W. Post, General Foods).

He was a friend of Stilson Hutchins who was the founder of the Washington Post. He had one of the first phones in the private residence and his business. W29 and W1729 were his phone numbers. The 29 was for the variety of pies he sold and I think the 1729 was the year the Copperthite family first came to America.

Henry was a Horseman of the Year in 1903. He co‑founded the Brightwood race track where he served as a judge, treasurer and events coordinator. When it closed on its final season, the crowd, mostly working men and women called for an encore that lasted two hours after he had gone home.

That year, he also sold a horse to Cornelius Vanderbilt for a record sum.

“By leading exemplary lives, struggling valiantly against poverty and adversity,” he was what in today’s society many think is a myth portrayed in the many Horatio Alger stories of rags to riches. A penniless but uncommon man who became a citizen, who prospered, who was decent, a Freemason when being so was the measure of the man.

He was a sportsman, entrepreneur, fought for his country, employed his family, became one of the wealthiest men in America. Henry C. Copperthite helped shape his town and his city. He was buried in Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown, West Washington.

Constance: Wow. And who is your great great grandfather?

Mike: He was Henry Copperthite, Jr. died of asthma at age 33 but he served in the Spanish‑American War when Theodore Roosevelt was a rough rider.

Constance: So the Henry that…

Mike: Is my great great grandfather.

Constance: Did all that you just talked about?

Mike: Yes.

Constance: He could not have died at 33.

Mike: No, he died at age 78 in 1925.

Constance: So he was your great grandfather.

Mike: That was my great great grandfather.

Constance: Great great…

Mike: The person I just talked about is my great great grandfather. My great grandfather was his son and he passed at age 33.

Constance: Oh, OK. All right.

Mike: And he was a rough rider.

Constance: So the great great grandfather lived to be 80…

Mike: 78 years old.

Constance: 78 and did all that in that lifetime?

Mike: In that lifetime.

Constance: OK. So for the purpose of this interview, I would like to focus on the Georgetown part of it. I see that you have in front of you a list of the buildings that were owned by your great great grandfather starting in 1886 and the last one listed is… What’s on there at the bottom?

Mike: 1935.

Constance: 1935. And are there how many houses on that list? How many buildings? 11?

Mike: Because some of our home blocks we didn’t count… there’s 20 here.

Constance: OK.

Mike: And I’ve been told by my great aunt that we probably had another 40 to 60 lots and/or homes.

Constance: 40 to 60 lots plus the ones that are listed here…

Mike: Plus 25 acres of Rock Creek Park…

Constance: 25 acres of Rock Creek Park and Teddy Roosevelt Island.

Mike: That stays on the island.

Constance: OK. So what we’d like you to do is starting in the year 1886, tell us again what brought him here and I know that he’d been in the food business before as a delivery person. Is that correct? Then he realized there was a real need for that in the nation’s capital. Paint a picture for us. Was he married at the time when he moved… Oh yes, he was because your great great grandmother said West Washington which is now Georgetown would be a great place to settle. So she was pretty much something as well. It sounds like they had the foresight to see that this is a great area.

Mike: I pulled her will. I haven’t found direct linkage to them for the suffrage movement but she had a will back when women were considered chattel. It’s a significant will. It’s in the national archives. She ran his businesses, his construction company. What they did was a lot of the wooden structures in Georgetown that were built in the last 100 years, they would purchase residence for people to live here.

Constance: The name of the famous pie company was the Connecticut Pie Company?

Mike: It was Copperthite Pie Baking Company and the Connecticut Pie Baking Company.

Constance: So two different companies?

Mike: They have two different entities‑‑ primarily sold wholesale. There was very little retail and if you knew where the social Safeway is now, that was actually a Piggly‑Wiggly going back into the 60’s and it was actually the first grocery store in Georgetown and it was called the West Washington Sanitary Grocery because sanitary was the key buzz word. He went to a fresh market everyday and he baked everything else. The whole coming of groceries and buying prepackaged products was relatively new. It came on with better transportation system, with refrigeration, the industrial revolution, the ability to…

He was trying to turn out 50, 60 thousand pies a day. They cooking pies in less than eight minutes. So they were steamed. The fruits going in the pie were steamed. There was a huge pie baking convention in Washington in 1912, 1911. This is library information. All the techniques and everything were brought in here.

He liked it when he was stationed here to protect the city as a soldier. He saw it as a great place to establish a business. He learned the pie baking business inside and out. That was… Pies in America in 1906 was you had two desserts that you didn’t make yourself. That was ice cream and pie.

He was at the forefront. He was the second largest or third largest pie manufacturer in the United States at that time. Here in D.C., that accounted for a lot of other factors. 60,000 pies a day was his capacity.

CT pie eating contest

CT pie eating contestTidal Basin Beach Club 1921

Constance: Why would people not want to make pies themselves?

Mike: He did a whole ad campaign on how convenient, you pick it up on your way home, ladies take your time off your hand, pick a fresh pie everyday from the local groceries because we guarantee you and we bring them there. Mostly pies were done with either jelly preserves that you kept or during season, the fresh fruit season, he had the ability though his transportation system to bring goods to his factories everyday.

Constance: It sounds like he also bought the land to have the fruit trees and the dairies to make the products for the pies and their crust so he provided his own materials. Is that correct?

Mike: To a large extent. He owned all the dairies in Maryland and the Shenandoah Pride people… If you look into our family, they married their friends and relatives so they crisscrossed each other’s paths in genealogy but you know Shenandoah Pride, if you go to 7‑11 today and you buy milk, is our family’s dairy.

Constance: Was he from Connecticut? Is that why the name Connecticut came to it?

Mike: He came from Antigua at 18 months of age. He was not a citizen of the United States. The 79th Highlander troop in the Civil War advertised that if you joined up and you served three years in the duration of the war, you’d be a citizen if you survive the war upon completion. So he was a farm boy in Connecticut, stationed at Georgetown College when he was down with the Grand Review of all the troops in Pennsylvania Avenue. He went home as a citizen back to Connecticut. So he calls himself a man from Connecticut.

Constance: He was in the Civil War?

Mike: He was in the Civil War.

Constance: And he passed through here after the Civil War and liked it?

Mike: He was stationed in Georgetown College for training to protect the college. And they then did a Grand Review of all the union troops and discharged, at least his company in Washington and on Pennsylvania Avenue. He became a citizen of the United States.

Constance: Did he go to college?

Mike: He did not go to college. He did not go. When I looked into that… When I first was trying to find out why my family wasn’t remembered or known in Georgetown, time passed them on, it wasn’t that he was… He was a pure Corcoran, but one of his lawyers and business partners argued the supreme court of every major case in the United States at that time. He was a friend of Teddy Roosevelt. He was a friend of William McKinley. They served in the same Masonic lodge together. I don’t think the college was the barrier there. He was totally… He was working class, but Georgetown back then was mercantile class.

There’s an article in 1980 something that I had in here that talks about Georgetown being the wrong side of the track, and it was. It was considered. Only at the time of Henry Copperthite that some of the more prominent beings that helped shape the city started living here. It’s where the commerce was. It was the commerce hub. All you have to do is look at the dome of the farmers and merchant’s bank, which used to be the old Rigss bank and you know that it was a hub. Dean and Deluca used to be a slave pen.

Constance: Let’s go… Let’s go for a moment to the buildings that your father either owned or was prominent in. You’ve mentioned a couple in the write‑up that you gave me. Talk about the pie company office at Georgetown Park. That one and what is now Benetton’s on the corner and the old bank building there. But if you would start with the one that’s opposite, if they built it, on what year was that built and what that was also the one on Wisconsin and M, I mean Wisconsin and P where you have a lovely picture which we hope to include in this record of the horse‑drawn pie wagons lined up. If you could talk about what specifically in Georgetown those three building at the very least?

Connecticut Pie Co at

Connecticut Pie Co at corner of Wisconsin and O

Mike: It started out in 1407 32nd street. He built a 75‑horse stable which was fire proof back in the day. The stables were above the carriages so you had an elevator that would take the horses up.

Constance: That was 1407 32nd…?

Mike: That was 3158 O Street. He owned mostly the whole block in there. On both sides of the street. If you can see…

Constance:

Where were the stables? Which one?

Mike: They were at 3158 O Street.

Constance: OK.

Mike: And if you see the row houses, apartment buildings over the slave penn, there was actually an article that describes the officer who got injured by falling debris and the permits that were built for that. The Potomac Savings Bank which was the new Potomac Savings Bank back in 1899 and 1900 is at the corner of M Street and Wisconsin where the Benetton store is now. Adjacent to that is the Masonic Lodge which he helped fund the building of that building. His factories built in 1914 were on M Street and that was from 3287 to 3289 M Street [read original Washington Times article click here] which is almost directly connected to the Benetton building.

Copperthite Pie Baking Co.,

Copperthite Pie Baking Co.,3289 M Street, NW

Constance: Same side of the road?

Mike: Same side of the street. Opposite side from Georgetown Park.

Constance: Let’s talk about your residences as well. There’s quite substantial residences on N Street, if you could list those loud and clear and N and O…

Mike: Those were my… OK, 3335 was my great great grandfather’s home, 13‑room house.

Constance: Did he build it or he did the…?

Mike: He built it.

Constance: That’s 3335.

Mike: That one he did not build. He renovated.

Constance: OK.

Mike: And then my great grandfather lived at 3337.

Constance: The Pie street address is 3159 O Street. Now when you say pie company address, is that the factory?

Mike: It was like a retail outlet.

Constance: That was the retail at 3159 O Street. Then you also had presence at 3275 Prospect? What was that building?

Mike: It was one of my relatives’ homes. Either my grandfather or my great grandfather.

Constance: Did they build it?

Mike: They built it.

Constance: In 1907?

Mike: Yeah.

Constance: And then two homes were being built on O and Wisconsin. Is that in 1908?

Mike: In 1908 and those were for family members.

Constance: Mostly brick?

Mike: Mostly brick.

Constance: Mostly brick.

Mike: But he had a construction company and he made loans to working class people so everything… If you go through the park… If you are on N Street and you go to a dead end, you have to take the exit down the park, all of those wooden structures that kind of not really big, maybe 700 square feet or less, those were built for employees or family members, distant relatives…

Constance: For his construction company?

Mike: For his construction… And then he sold… If you didn’t know him and you wanted to buy a house and didn’t know what to do, you saw an ad in The Times, The Post and the other newspapers, you could go and apply and have a house built for you. He did a lot of construction.

Constance: At that time, was there a lot of housing for the people who were actually the laborers of Georgetown in Georgetown at that time?

Mike: There wasn’t so they started building that. In the 1890’s, there were a lot of shanties along the river. He wasn’t the only one. I don’t think he was the principal if you do researching online about… but he had his own construction company. He had his own developer.

Constance: But once they started building, was it common for the laborers to live in Georgetown?

Mike: They lived in Georgetown but Georgetown mostly became…This side of Tiber Creek before Rock Creek Park, a lot of laborers came across. Georgetown had a planning board and you can google that anywhere and they were trying to set civic association meetings. They were trying to raise the standards of Georgetown and trying to make it a mercantile class, up and coming young businessmen.

Constance: Around what year was that?

Mike: That was about 1905 to 1909, 10, 11.

Constance: Did it work?

Mike: I think it did.

Constance: Yeah. Well, to continue through the houses that your family built, is that 3134 and 3135 O Street?

Mike: Yup.

Constance: The Peter’s Mill Seat?

Mike: 25 acres.

Constance: 25 acres of Rock Creek near national zoo. Peter’s Mill Seat. OK, that’s over near the zoo. And then you move up to Valley Street, wherever that is. 1618 Valley Street?

Mike: That was my great grandfather, not my great great grandfather. That was his house, residence.

Constance: Where is Valley Street? Is that in Georgetown?

Mike: It is.

Constance: It is really where?

Mike: I have no idea.

Constance: OK. Valley Street, 1618…

Mike: That’s where he snuck off and married one of the workers in the pie factory and that’s the romance of the pie factory story.

Constance: The romance of the pie factory story that Henry Jr. snuck off with and married a pie factory worker and there’s an article about it that we’ll also include in the record. At the store… they got married at the store? What did you say?

Mike: They snuck over. They got a friend to get them a permit. They were underage at that time and they were married at St. John’s.

Constance: At St. John’s. OK, so your great great grandfather was, you said, quite contributor to a benefactor of St. John’s Church on O Street. Is that correct?

Mike: Yes.

Constance: Here we have principal in the Analostan Improvement Company which I’m really impressed…

Mike: It was called Analostan back in the day. Before that, it was Mason’s Island. Before that, I read that it was called Algonquian.

Constance: Yeah. Did he own… Was he an owner?

Mike: Only 75 acres.

Constance: 75 acres.

Mike: It was everything to the water.

Constance: On the island itself and then did your family contribute that to the national park or was it done like…?

Mike: I was always told we donated it to the Roosevelt but I found an article where Henry sold it. His share for 20,000 dollars in 1928 to the Roosevelt…

Constance: To the Roosevelt Trust…

Mike: Yeah, which is a lot of money.

Constance: Yeah.

Mike: Just a little side bar story. I have Labrador retrievers, my first one given to me by Bo Herman, my neighbor and I was a child. And Teddy Roosevelt island is around in the national park but I always let my dog run free because it’s near the river. One day, park police came over and asked me to leave and I said no no no, I’m grandfathered in because my grandfather Henry used to own this island and that story has worked a zillion times. Nobody has ever questioned me after that.

Constance: Wow. That’s a good story. To continue with these houses that he built for your family, 3287 and 3259 M Street, 30,000 square feet. Sorry, correction. That was 3287 and 3289 M Street, 30,000 square feet?

Mike: Correct.

Constance: So that’s the corner of M and 32nd, what buildings in them?

Mike: It’s listed in here. I just…

Constance: OK. And then Delight In Every Bite Copperthite Pie Company…

Mike: 1045 Wisconsin Avenue.

Constance: 1045. Is that the one at Wisconsin and P?

Mike: No.

Constance: That’s the one down the corner?

Mike: Yes… No, that one down in the corner is just an expansion.

Constance: So there’s another one? This is the…

Mike: I think he owned… and not counting the reconstruction… probably nine structures. During World War I they were turning over every day to ship that’s why the shift he built factories in Richmond, Petersburg so that they could ship goods abroad.

Constance: Were they pie factories?

Mike: There were pie but they also did the hardtack bread.

Constance: Oh, the hardtack to go off to the war.

Mike: And there’s two schools of thought why they call them dough boys. One is the Spanish‑American War, they got dust and dirt in Mexico and they call them dough boys and our family claims they called them dough boys because we provided the bills to provide the hardtack…

Constance: What is hardtack?

Mike: Like a bread or a biscuit that they salted… I’m not an expert on that. I just found that by reading places. That would make sense because he was a board member in the Newport News ship and they were all going off to World War I…

Constance: So he had three factories, Newport News…

Mike: He had multiple factories. He has Baltimore, two in Washington, one on Capitol Hill, Richmond, Petersburg, and Newport News.

Constance: You also mentioned that they say in an ad, it’s Connecticut.

Mike: In 1889.

Constance: In 1889, 12,000…

Mike: 12,000 pies a day then.

Constance: 12,000 delicious pies every 24 hours in 1889 to the residents of Washington?

Mike: Yeah. In this article, you can read… and this is an advertisement he took out. In New York, the capacity was 35,000 pies a day.

Constance: There’s also a picture of members of Congress each with pies in their hands, standing on the steps of the Capitol. It looks like…

Mike: The first woman member of Congress…

Constance: And the first woman member of Congress eating pie.

Mike: They had a drive to raise money for the support of World War I and he spearheaded the drive and raised 300,000 dollars in about a week in Washington. This is one of the ads he took out – the Connecticut and Copperthite Pie Company.

Constance: So he raised money for the war.

Mike: Pension relief.

Constance: That’s at 3159 O?

Mike: Yes.

Constance: OK. We will include scans of these that people can see in record with the interview. Now this has on obviously 3237 M Street, did your great grandfather build this house?

Mike: He renovated this house. I think it pre‑dated him.

Constance: This is on Cox Row…

Mike: That house right there…

Constance: On the cover of Maroon’s Georgetown is the house that they renovated. What year would that be?

Mike: I would say 1906.

Constance: 1906 and did you grow up in this house?

Mike: No. I was at 3035 N Street.

Constance: 3035 N. Back to your great grandfather and all the amazing things he did in Georgetown, what can you tell us? I see he was a sportsman, obviously he had a construction business, he obviously had the pie business… How many children did they have?

Mike: He had eight children. He was only survived by four of his children. His daughters that survived… In Richmond society today there’s a famous name of… I’m drawing a blank right now but… Dr. Shelby Foote talks about the Civil War cavalry commander. He wanted his daughters to marry into society because he did not have any formal education so one of his daughters married the son of the governor of Connecticut. My daughter is downstairs. Her name is Keely Alexa Crittenden Copperthite. There’s a Crittenden Street in Washington.

Senator Crittenden was the senator who tried to and got past the Crittenden compromise and Missouri compromise which tried to stop the onslaught of the Civil War I don’t need to go into that.

Constance: Yeah, we don’t need to do that but more of what we like to hear about is if you know anything about it was did his eight children go to school here in Georgetown? Did they grow up here? Did they grow up somewhere else?

Mike: I didn’t go to Georgetown because they dropped the wrestling program and I was a wrestler.

Constance: Yeah but your great great grandfather’s eight children?

Mike: His kids went to Georgetown. He helped endow, and his partner was Mr. Smith. I don’t know if you know the Smith Center in Georgetown. I’m literally on the beginning of this research. If I had the time, it’s a who’s who. The book upon that shelf that says the centennial commission of the District of Columbia in 19… whatever centennial year… 18… 1911 maybe. That was himself, Henry Copperthite, and his peers and his business partners and they are the descendents who’s who of almost every cornerstone of this building in this town and city today.

Constance: What I’m kind of getting at is more of what life was like then. If you could paint a picture of these kids of this amazing man who is all over the place in business and in social…

Mike: I included a story of his one son, Henry Jr., when he was a young lad. He and Henry Sr.’s brother’s kids, so that would be Henry Jr.’s cousins, all took horses from the stables and marched over to the White House in 1903 and knocked on the door and asked if young Kermit Roosevelt could come out and play. The article in The Washington Post said “Young Rough Riders Call on the White House for Play” so there’s a story of…

Constance: And did he?

Mike: He could not but he waved from the window and Mr. Roosevelt promised his son would come out and play at a later time. Now Kermit Roosevelt was killed in World War I later, much, much later as a soldier and devastated the President of the United States at that time. There’s another story where the Copperthites went with other kids on a scouting trip to Roosevelt Island and they went looking for Pirate Billy the Kids’ treasure. The park was written up in the society and news worthy notes in Georgetown back in the day.

On hunting trips that my grandfather made to North Carolina and to Florida, they’re showing the trains and the boats and the places that he stayed along the way with relatives. Some of the Crittendens from New York came down to stay in Georgetown, There was a White House gala and a dance and that’s written up in the society pages with Corcoran and other folks attending with their daughters.

Constance: So they found some time to play? They sounded like he was just really busy.

Mike: The story about how fishing was bad along the Potomac because of the weather and those who learned the leisurely craft of fishing such as Henry Copperthite were out there in their waders fishing and enjoying themselves. A lot of what they did was inside the city. The summers were oppressive. They didn’t know how people got malaria. Georgetown was a swamp. The Washington Gas Light Company was the main, you know the tanks and holding companies down along the river… so they all fled the city during the summer.

They didn’t know… The windows that have screens were really closed and there was oppressive heat or the windows were open and bugs got in even the wealthiest in Georgetown So they all fled. They went to… We had a hotel in Cape May, New Jersey. Francis Scott Key used to go not to our family’s hotel but it was in Cape May.

Henry built Burke, Virginia as a retreat which everybody from McLean who was funny. I should tell you a side story. McLean, Virginia is not named after the person everybody thinks it’s named after. It’s named after the son who got run over on his way home drunk on Wisconsin Avenue in 1903. Probably one of the first people in America to be run over by a car.

Constance: Who was run over?

Mike: The person who did all the industrial stuff was Mr. McLean. He built this boiler for steam ships and for factories back in the day. He made the money. His son then who an heir to the wealth acquired and bought The Washington Post from Mr. Hutchins who was a friend of my great great grandfather. He was married three or four times. He had two sons and both of them really didn’t amount to much. Mr. McLean loved horseback riding when he’s not at the Washington Post and you can’t find much of this maybe. The Washington Post has expunged a lot of those records. McLean was fond of horseback riding and show horses and McLean had a house up there and stable horses up there.

Constance: Back to Georgetown, did your great great grandmother also live to be in her…

Mike: She died in 1921. She was either 69 or 70 when she died.

Constance: And what do you think, in your great great grandfather’s personal writings maybe, what do you think that he would like to leave behind of all that he’s done in Georgetown and all the businesses he had, what do you think he would like to say about his life?

Mike: I think he was for child welfare and animal rights. He was a Mason which was one of the forerunners of the unions in the United States, not those little guys in hats who run around in parades. He was progressive. I would suspect he was a Democrat though he was friends with…. He helped found what became the AFL‑CIO. I think he was an industrialist, entrepreneur. He was committed to his church. He’s committed to his family. He’s committed to his community. I think he made provisions to take care of his family as much as he could into the future. I think they were all very excited about being Americans.

He seemed like a great guy in everything that I’ve read. I cried when I read the story about how they gave him a two‑hour standing ovation when the track closed down and they brought him out. They said he had gone home for two hours but they were still cheering for him.

Constance: The track in Burke?

Mike: No, the one in Brightwood which was a few blocks from here. It was a huge track.

Constance: Tell us about that.

Mike: I don’t know much about it except… Mr. McCoy can probably tell you more about it.

Constance: So there was a race track here that he’s part of…

Mike: The race track… Mr. McCoy do you know exactly where Brightwood was? Was it the 16th near the White House, north of the White House?

Mr. McCoy: No, it was all on 7th Street, the Brightwood neighborhood, near Military Road intersection with 7th Street. That’s a part of the neighborhood.

Constance: So the Brightwood…

Mr. McCoy: The information on that is at the Washingtoniana Room.

Mike: Thank you very much.

Constance: So the Brightwood race track was off Military and 7th …

Mike: And there was like a merging of professional race circuits, so there was Kentucky circuit of pacing and trotting and there was a New York circuit and there was a fair circuit. So he was co‑founder of the Brightwood Racing Club, as what they call themselves. It’s in the…

Constance: Did he do that for pleasure or do they feel it was good business? What do you think the whole racing…

Mike: I think he did it for pleasure but I also think he was a heck of a promoter. I found articles in Iowa where he had motorcycle races at his track. He had a room for 30 years at the Willard hotel which he used for entertaining and for guests and things. He was promoting his businesses and his company. He was trying to, I don’t want to say improve his lot in life because I think he was a marvelous man by anybody’s standards.

Constance: Is there anything else? I know there’s so much history here and we will post, perhaps, the written history that you have given to us.

Mike: No. His descendants, as I said at the beginning, there’s 27 of us in national cemeteries who fought for our country and every war. You could almost do a forced thing of our family. There was a James Copperthite who was on the Titanic who died as a firefighter. There was a James Copperthite in 1700 who was part of a mutiny of a British ship and ended up in Connecticut. And then there are members of my family that pre‑date Henry Copperthite coming from Antigua and his family, Thomas, who was his father, to Connecticut, who became a citizen in 1887. But the descendants, my dad, his brother, my grandfather and uncle. My grandfather worked in the war department during World War II. My uncle served in Korea as an army. My father was in Korea as an air force pilot, was awarded a Purple Heart. I have in that file folders my cousin who’s silver star and his nickname was Bunky Copperthite. If you see the move Apocalypse Now, the character Robert Duvall was based in part on his crazy antics in the military.

Constance: And you still own some properties in Georgetown?

Mike: We own three properties in Georgetown.

Constance: And are a lot of your descendants buried at Dumbarton Oaks?

Mike: The name Copperthite there’s only 12 people buried because Henry had four daughters and then he would get into the McCoy’s… I’m drawing a blank… Vandussen. There are probably in Oak Hill Cemetery 28 or 29. Last one, Henry’s oldest son was Myron who was buried in 1962.

Constance: But your great great grandfather is buried…

Mike: In Oak Hill Cemetery.

Constance: In Oak Hill Cemetery.

Mike: Along with his wife and seven of his children.

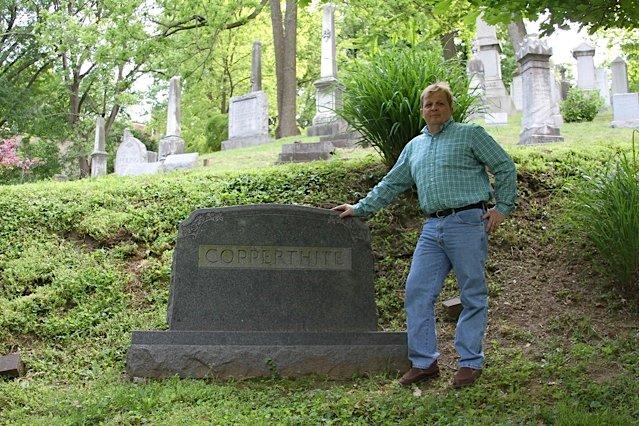

Constance: Just stop here. We have some time. You want to take the walk up there and get a picture of you by your great great grandfather’s…

Mike: Sure, I was hoping that. You know the tour that’s going on? Is it open right now? He’s in 477… 4755. This is…

Constance: Let’s go up and see.

Mike: Sure.

Constance: OK. This is the conclusion for now. We’ll go up and see if we can see the grave site and I’ll take some photographs up there of the great great grandson who was kind enough to give us the interview here today. That’s the conclusion at this point.